He is the first person we see, basking in a blinding sun while awaiting ordersan apt metaphor of allegiance to the emperor. It is Kadokawa’s wide-eyed inexperience that most closely parallels the viewer’s stance of open-mouthed disbelief. Tang, his loyal, self-sacrificing secretary, represents China and Kadokawa, an infantryman in the Imperial Army, Japan. This it does by highlighting the fates of three characters, representing the key political forces: Rabe, the German leader of the safety zone, stands for “the West” while Mr. No doubt both the positive and the negative reactions reflect the film’s formulaic trappings, as well as its efforts to placate all interested parties. And though domestic critical reception there was mixed, the film was praised at Cannes and other film festivals in Europe and North America. While the visceral immediacy of such images, intensified by black-and-white cinematography and handheld camerawork, recalls such classics of historical reenactment as The Battle of Algiers (1966), as well as authentic frontline documentaries like War Photographer (2001), City of Life and Death also courts an audience more responsive to spectacle and emotional manipulation than to mere facts and testimony, a strategy that helped make it (under the title Nanjing! Nanjing!) a box-office hit in China. As chaotic as they are craftily choreographed, these sequences infuriate even as they paralyze response. Later, as the camera moves through the corridors of the hospital in the safety zone, registering the desperation of those making pathetic appeals to protocol, it is driven by the relentless surge of intruding soldiers as they shove interfering staff aside, murder patients in their beds, and throw a child out a window.

Through this meticulously staged rout, Lu’s mobile camera alternates between wide-angle views of the inner city––an astonishing achievement of set design––and subjective perspectives of Chinese soldiers evading or firing on the Japanese. In its first forty-five minutes, the film reenacts the siege and fall of the city and the decimation of the Chinese army as tanks bombard the citadel.

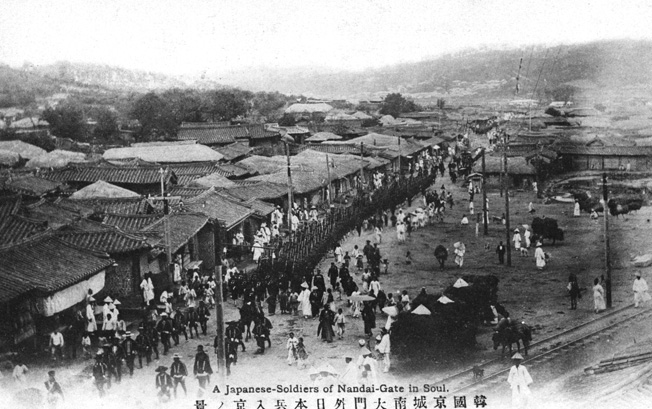

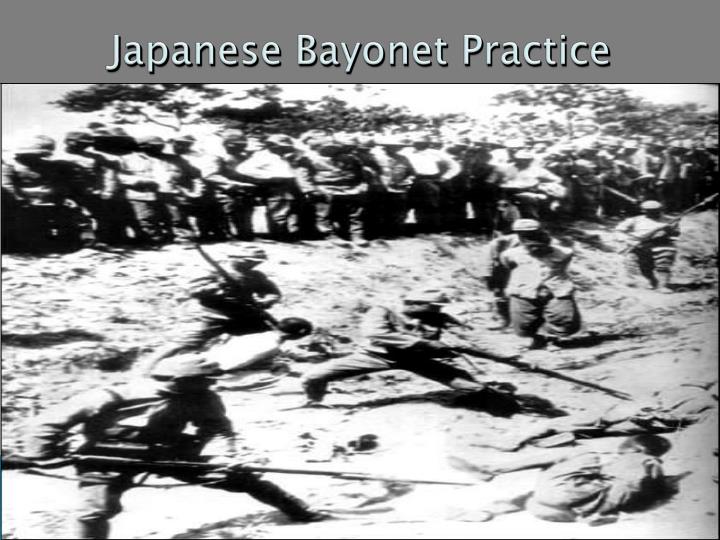

In City of Life and Death––which opens on May 11 at Film Forum in New York––Chinese director Lu Chuan hurls the viewer into this nightmare with virtually no explanatory context, evoking a sense of the confusion, shock, and horror that must have swept over the inhabitants of Nanjing. Wilson, a surgeon, and Minnie Vautrin, head of the Ginling Girls’ College of Nanjing. These included the German businessman John Rabe (whose valiant efforts to save lives have been compared to Oskar Schindler’s) and two Americans: Robert O. But much of what we know about the “Rape of Nanking” comes from the diaries of Westerners living in the city who established a safety zone for refugees. Many incriminating photographs of the events exist, as well as footage of the torture and killing, taken by Japanese soldiers betraying no qualms about leaving a record of their behavior. Surrendering Chinese soldiers were buried alive or massacred in the middle of the city, thousands of women and children were raped, and more than two hundred thousand civilians were killed. ON DECEMBER 13, 1937, the Imperial Japanese Army, having laid siege to Shanghai and other cities, invaded Nanjing, capital of Nationalist China. Lu Chuan, Nanjing! Nanjing! (City of Life and Death), 2009, stills from a black-and-white film in 35 mm, 132 minutes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)